.jpg)

The history of High House as a building, and of its occupants

Last updated 25/9/2023

To celebrate the clubs 75th anniversary in 2009, a commemorative book was written detailing the history of the club. Included in the book were a chapter on the history of High House as a building, and a chapter on the occupants of the building as a dwelling. Because the book was restricted in size to 248 pages, the size of these two chapters had to be condensed, so this document puts the two chapters together as a full combined history.

The name High House implies that it is the dwelling higher up the valley than the existing ones, and so we can assume that whenever the buildings at Seathwaite came into existence, the ones at High House came later. We know that Seathwaite existed as early as 1292 from a written source, though it was spelt as Seuethwayt meaning ‘the clearing where sedge grows’ from the Old Norse ‘seave’ meaning sedge, and the Old Norse ‘pveit’ meaning clearing. Hence High House probably came later than this.

Using the various sources shown at the end of the document, we can piece together a documented continued occupation of High House from the mid 16C to the end of the 19C. It’s strange to think that in our use of High House in the 21st century, we are treading in the footsteps of generations of people going back to at least the mid 1500’s. Looking back over those generations, the links with both the hamlet of Seathwaite and the Wad Mine on the slopes opposite becomes apparent, and both of these will be touched on in this document.

Prehistoric landscape

11,000 - 4500BC. Following the

retreat of the ice after the last glaciation, dense woodland developed to an altitude of

approx 700 metres in the Lake District and by C6000BC most native trees are

thought to have been present in Cumbria with extensive areas

of alder in hollows where the drainage was impeded, both in the valleys and in the

uplands. Throughout most of Cumbria oak was the dominant tree in the drier parts of

the valleys extending up into the uplands, with elm to be found growing at

intermediate altitudes.

4,500 - 2,300BC. The Great Langdale stone axe factory extended over into Borrowdale with sites grouped at intervals near the Seathwaite Fell Tuff outcrops which continue west from Great Langdale to Scafell Pike and north to Glaramara.

2,300BC - 700BC. A funerary cairn has been postulated at Styhead Ghyll on land rising up by the ghyll onto Seathwaite Fell. It was substantial in size (but has collapsed and been eroded on one end), measuring over 20m in diameter and between 1.5m and 3m in height, with a central depression possibly reflecting antiquarian disturbance. Another possible funerary monument is a putative ring cairn on Hind Crag which measures some 5.5m in diameter with a skirt of large angular boulders covered over with a low bank of smaller rounded stones.

700BC - AD410. There is very limited evidence for Iron Age activity in Borrowdale, though there is the Iron Age fort of Castle Crag. It was this fort that prompted the 10C Scandinavian settlers to name the valley Borrowdale – from Borg (fort) and Dalr (dale or valley). The only definitive evidence of Romano-British occupation in the valley derives from Castle Crag where pieces of Roman Samian and other pottery, along with smelted ironwork slag, have been found. In addition, a coin of the Emperor Nero was found in Borrowdale in the 1970s, along with other unidentified coins,

AD410 - AD900. Little evidence of Saxon activity has been found, though a 7C Northumbrian saint, Herbert, had a hermitage on an island on Derwentwater, and the island is still called St Herbert’s Island.

The Medieval Landscape

Scandinavian settlers arrived in Borrowdale in the 10C and named many of the geographical features around them. In fact, the place names of Borrowdale are so dominated by those of Scandinavian origin that it is difficult not to draw the conclusion that it was the Scandinavians who were the first group to firmly establish themselves to any extent in the valley. Particularly common are the names that include the element ‘thwaite’, meaning 'Forest land cleared, and converted to tillage; an assart', which suggests that the Scandinavian settlers found much of the valley uninhabited or sparsely settled, with the valley floor thickly wooded compelling them to create clearings.

Many of the local place names that we recognise today came into being during this period, though two have changed completely. In 1209, Sty Head was refered to as Edderlanghals - see below - and Sprinkling Tarn which in 1322 was known as Prentibiountern.

By the time of the Norman Conquest, the whole of the area that we now know as Cumberland and much of Westmorland was under the control of the Scottish Kings, and because of this the area was excluded from the Domesday Survey of 1086. Prior to that, the area had been in the Kingdom of Northumbria, and before that the Kingdom of Strathclyde. It was only after the conquest of 'the

land of Carlisle' in 1092 by William Rufus that the land came under Norman control

and they were able to establish large feudal baronies - see map below. The extensive areas of forest can be readily seen.

The first record of the term Cumberland appears in 945, and both Cumberland and Cumbria derive from the Brythonic Celtic word 'kombroges' meaning comapriots.

At the end of the 11C, William II gained control of the area, and the resulting territorial reshuffle under Henry II led to the creation of the counties of Cumberland and Westmorland/Westmoreland.

The period from 1100 – 1350, was one of economic growth and rising population, achieved in the north-west mainly through the foundation of monasteries. Furness Abbey was established at Barrow in 1127, and in 1209 they bought the greater part of Borrowdale including the Seathwaite Valley for £156 13s 4d from Alice de Rumeli, the heiress of the barony of Allerdale. The rest of Borrowdale to the east was owned by another great Cistercian monastery, that of Fountains Abbey near Ripon, and in 1211 a document detailing the boundary between the two abbeys was drawn up. The land would have been used as grazing land known as granges.

A dispute arose in 1301 between these two monastic foundations as to who owned Stonethwaite, as it lay on the boundary between them, and from the resulting court records we know that Stonethwaite was a thriving dairy farm. This fact may have had something to do with the cause of the dispute as the monasteries at that time were the leading agents in the international wool trade: an early example perhaps of trade wars! The dispute bounced around various courts before finally going up to the king for resolution. He confiscated the land and sold it to the first bidder, which was Fountains Abbey, who bought it for forty shillings. Besides farming, another activity carried out was the mining of iron ore by Fountains Abbey from nearby Ore Gap under Bowfell and the head of Grains Ghyll, which is likely to have then been taken down to bloomeries located in Langstrath.

The imposition of forest laws on much of the Lake District after 1066 restricted agricultural improvements in a time of rising population. They were designed to protect wild life for the huntsmen, and a map of the medieval forests in this area shows that the Derwent Fells Forest covered the land west of Borrowdale from Cockermouth to Honister, and the Copeland Forest from Honister down to Eskdale. Hence we can assume that most of the Seathwaite Valley would probably have been forest right up over Sty Head.

Roads in these times would have been rudimentary. A document in 1280 records the grant by Adam de Derwentwater of rights of way from Borrowdale to Fountains Abbey, one route by Ashness, Castlerigg, and Shoulthwaite to Dunmail Riase, and the other by Watendlath, Harrop, and Wythburn. Other roads were over Stake Pass to Langdale, over Styhead to Wasdale, and one in 1294 called Le Cauce ( the causey) running up Grains Ghyll. A 'causey' is an Angle-Norman word caucie meaning a causeway or possibly a cobbled track.

That by the end of the 13C land was being cleared in the Seathwaite valley is partially confirmed from recent investigations in the valley below Stockley Bridge. This work indicates that around that time, both sides of the valley were covered in partially cleared deciduous trees showing the start of a program of clearance. Excavations have revealed the remains of a wall and a fence indicating that the farmers were extending their cultivated areas by enclosing the land around their farms. In 1418, according to the Fountains Abbey survey, there were 41 farmsteads in Borrowdale each with an average of 3 acres of enclosed land. Additional evidence is provided by the first documented recording of Stockley Bridge in 1285, Stockley being Old English for ‘tree-stump meadow’. The route of Sty Head being an ancient one linking Borrowdale and Wasdale is illustrated by the fact it was given a name. The earliest reference seems to be that quoted in the Place Names of Cumberland - Edderlanghals (1209-10) in which Edder may have been swift, referring to the cascades of Sty Head Ghyll, and hals being Old Norse meaning nick or dip in the ground. Nowadays we would say pass or col.

Account books from Fountains Abbey show various payments relating to Borrowdale from this period, including the Bursars Book 1456-1459 and Memorandum Book of Thomas Swynton 1446-1458 (Fowler 1918). These accounts refer to a number of economic transactions that clearly indicate that Borrowdale contained a significant number of cattle during this period. The fairly considerable sum of £17 6s 8d is recorded for the sale of hay, suggesting extensive hay meadows in Stonethwaite and payment of foresters wages by the abbey tells us that active forest work was also being carried out. Other entries include two payments for the construction of river embankments highlighting the fact that the problem of flooding in the valley is by no means a recent one! Farming with sheep was also carried out, though a statute in 1380 describes wool from Borrowdale as the 'the worst wool in the realm".

The general pattern of the farming landscape in the 16C was based on a system of open fields on the valley floor, where each farmer held several strips, which were enclosed from the fell sides by a ring garth wall, although the identification of physical evidence of a ring garth has been problematic within Borrowdale. Some historians have suggested that the typical farm of this period was of a small acreage growing oats, barley, and hay but with livestock husbandry as the principal occupation, with an average herd of between 10 and 20 cattle, a small flock of sheep, and a horse or two.

By the end of the 16C, the pressure on land for colonisation meant that most of the forests had been converted into the huge open grazing lands that we now call Commons. The Middle Ages ended with the start of the Tudors, but most effectively with the confiscation and sale of the monasteries after 1536, leading to the rise of the tenant farmer, including the Braithwaite dynasty.

The 16th and 17th Centuries

The earliest written evidence we have for the occupation and existence of High House is a Baptism entry for the year 1565 – “Thomas Braytwhat filius Guillelmi de Heehouse”. Written in Latin, this translates literally as ‘Thomas Braithwaite, son of William of High House’. As with the spelling of High House, there is variation in the spelling of people’s names. The family name of Braithwaite is one that is connected with High House and Seathwaite until the late 1700’s, and may derive from one of the many Braithwaite villages in the north of England, and in particular the one near Keswick, the place name itself meaning “broad clearing”.

After the clubs 75th commemorative book was published, Denis Mollison (Emeritus Professor of Applied Probability at Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh) contacted me and gave the club some interesting information regarding some of the inhabitants of High House obtained during his Jopson family research. He says that “for the will of Robert Jopson of Seathwaite in 1573, three of the four witnesses are called Brayhwat (or variant spelling), one of them being William Brayhwat of “Hee House”

We do not know when or where William Braytwat (whom we shall refer to as WB1) was born, or who he married, but we have a record of him producing two sons, Thomas born in 1565 as noted above, and John whose baptism is unknown. William died in 1580, and though we have no record of any will, it appears as though John succeeded him, either because he was the elder son being born before 1565, or because Thomas had died by this time. Certainly we have no further record of Thomas.

In Ian Tyler's 'Seathwaite Wad' he notes that around the 1590's, a barn owned by William Brathwaite in Seathwaite was being used to store wad, though this doesn't tie in with the WB above who died in1580.

John married Janet Birkhead, possibly of Seathwaite, in 1575, and prior to John’s death in 1609 they produced 7 children. William (WB2) was the eldest and born in 1577, two years after the marriage. He married Elizabethe (Elizabeth) in 1604, when aged 27. Elizabeth appears to have been a popular given name at the time, presumably as a result of the reign of Elizabeth I. The second child was Janet in 1580, who married Robert Birkheade of Seathwaite in 1608 aged 28. The third child was Esabell who was born in 1582, and we have no further record of her, perhaps because she moved out of the house due to marriage. The fourth child was John born 1582, and again we have no further record of him. The fifth child was Thomas born 1587, and he married Ellynore (Eleanor) Hunter who died in 1681. The sixth child was Ales (Alice) who married Thomas Gaitskell in 1618, aged 28. The seventh and last child was Elizabet (Elizabeth) who married a Gowen Norman in 1627, aged 33. In 1632, a William Braithwaite was brought into the lease of the Wad mine and it seems reasonable to assume it was the same WB2 that lived at High House, as the others who were also brought in were also local men: Robert Jopson, John Birkett, and John Fisher. Ian Tyler notes that a Fisher in 1566 led a band of ruffians in an attack on a wad miner.

We thus know that people were living in High House from the mid 16C, but it is very difficult to know what the building would have looked like at that time as there is little to compare it with elsewhere. In all likelihood, it would have been a very simple single storey building with possibly an external building for animals. It is natural to assume that the current main building was the original, with the men’s dormitory building being added at a later stage to hold animals, but why build it off-set from the main building? Whatever the reason, we know of no other similar off-set example in the Lakes area.

During this document, the building will be considered to have passed through four phases of development and these will be referred to in the text -

Phase 1: 16C or earlier. A very simple timber framed building with a thatched or turf roof.

Phase 2: Starting mid to late 17C. A traditional, or vernacular, layout as part of the great age of re-building in stone.

Phase 3: 1747. Re-building by Thomas Braithwaite as noted over the outside door.

Phase 4: 1933. The conversion by the Club

Of the next generation, we have records of Thomas and Ellynore producing two children, William who died in 1696, and John who died in 1621 as an infant. The succeeding line was of course the first born son William (WB2) who had married Elizabethe. They produced five children starting with Jenett (Janet) in 1608 who married John Wastell in 1628 aged 20. The second child was William (WB3) who probably married another Elizabeth. The third child John, born in 1630, married Margaret Vicars in 1747, aged 17. Jennett (Janet), the fourth child was born in 1639, with Robert the last child born in 1642. These last two children may be incorrect and part of another family, as the off-springs above imply two Jennets to the same parents, and WB2 would have been 62 at her birth and 65 at the birth of Robert. Both are feasible, but unlikely.

Being the eldest son, William (WB3) succeeded, and with Elizabeth produced three children: Thomas born 1646, Elizabeth, and Agnes. We know little about Thomas, but Elizabeth produced two children, Elizabeth and John, both names from the male ancestry.

In 1681, William (WB3) the husband of Elizabeth Braithwaite died, and in his will dated 1681 he leaves his son Thomas the following items - A chest in the outchamber, a cupboard in the bower, a long ladder, a spade, a hack, a crawmel or gavelock, a hammer, and a blocker, besides the sum of £4. He must have been reasonably well educated as he signed his own will, compared with other wills, even later, where the person merely signed their mark.

The ownership of the land prior to this period is unsure. As we have seen, most of the land of Borrowdale formerly belonged to Furness Abbey. One account says that the land then passed to the Dukes of Somerset, and then the Earl of Egremont. Another account says that after the dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII, they passed to the crown. Either way, in 1613, the manor of Borrowdale was sold to William Whitmore and James Verdon, Merchants of London for the sake of the minerals (including presumably the Wad mine). Two years later, they sold it to Sir Wilfred Lawson and 36 freeholders of the various farms, in what became known as the Great Deed of Borrowdale, a copy of which is in Keswick Museum. A letter from the Cumbria Record Office in Carlisle in response to a query, said that no original exists. The various freeholders mentioned in that deed may be of interest –

Sir Wilfred Lawson, of Isel, knight; Johii Lamplugh, gentleman; John Braithwaite; Robert Braithwaite; John Jopson the younger; Nicholas Dickinson; Thomas Birkhead, of Seathwaite, yeomen; Charles Hudson, of Boutherbeck [?], gentleman; William Braithwaite; John Fisher the younger; John Jopson; Thomas Fisher; John and Robert Birket; Anthony Braithwaite and Christopher Vickars, of Seatoller; Daniel Heckstetter, of Rosthwaite, gentleman; John Birket, of Thorneythwaite; Janet Richardson, of Longthwaite; John Youdale and Nicholas Birket, of

The Chapel; Edward, John, Christopher and Thomas Birket, all of Rosthwaite; Hugh Fisher and Gawen Harris; John Wood, of Skairness; John Fisher, of Grange; John Banks, of Stanger; John Fisher and Timothy Fisher, of Hollows; John Lambert and Richard Hyne, of Manesty; Wm. Howe, of Newlauds, yeoman; Wm. Braithwaite, of High House; and

Christopher Braithwaite, yeoman.

They reserved however the “Wad holes and the rights to work them”, referring to the wad also as “Black-cawke”.. It is partly this gaining of the freehold of property that enabled the great rebuilding in stone period to begin.

It appears as though the Lawson family took on the role of Lord of the Manor for his lands, which were probably centred around Seathwaite, Rosthwaite, and Stonethwaite, and it is likely that the holdings encompassed the greater part of the Borrowdale valley.

The period of mid to late 17C is known as the age of great re-building in stone, which generally occurred in northern England between 1650 and 1720. This rebuilding was the result of various factors including the union of England and Scotland in 1603 reducing border raiding; increased prosperity from the wool trade; and the new laws of inheritance that enabled farmers to become virtual freeholders of their property. So began the rise of the “yeoman” or “statesman” farmer – someone who owned and worked their small estate. This gave greater stability and confidence to rebuild small single storey dwellings into the characteristic stone built two storey farmhouses that we see today. To meet this demand slate quarrying began in earnest, and Honister Slate Quarries opened in 1643.

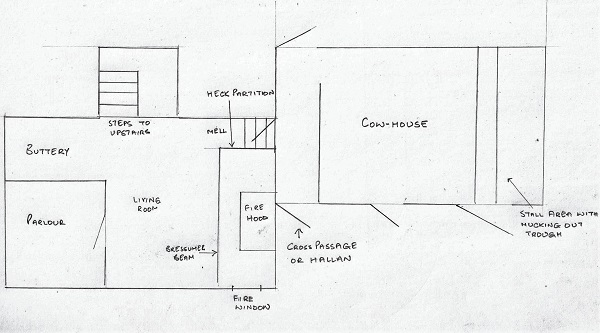

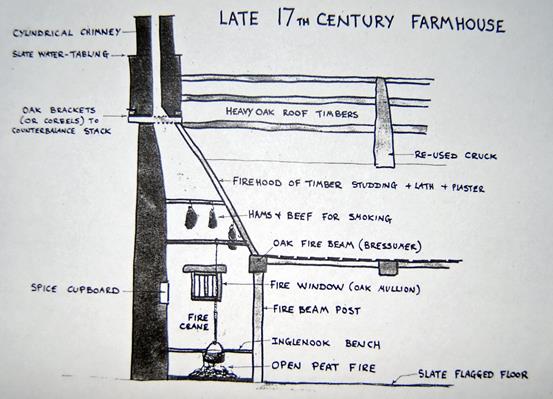

The conjectured layout above is a combination of the current building and what is considered to be the standard layout for a building of that period.

Between the House and the Cow-House would have been a cross passage called a ‘Hallan’, with a door off to the right into the Cow-House - what is now the Men’s Dormitory.

At a working weekend in March 2011, a doorstep was uncovered as an entrance to the far end of the Cowhouse. Subsequent work has uncovered a stall area with a central ‘mucking out’ passage.

Comparison can be made to a similar excavation made on behalf of United Utilities at a farm called Peel Place at Lanthwaite near Buttermere, where similar cobbling was found - see below.

The excavation work was carried out in conjunction with the National Trust, and following its completion they advised that the area should be recorded and then covered in sand to preserve it for future generations. This has now been carried out and the area grassed over.

A further door would have led from the Hallan to the left into the House. This would have led into a room called the Firehouse (the current Common Room) so called because this was the only room that would have had a fire. The current arrangement has steps from the Dormitory down into the Common Room but these are a later addition. Viewing the outside wall from the front of the Men’s Dormitory where it meets the Main House, the line of the original doorway of the Hallen can be plainly traced all the way down from the window ledge to the outside floor level. Note that to view this requires the movement of a lot of coal as the coal store normally occupies this corner!

The downstairs of the house would have been where the family lived, and would have consisted of the Firehouse where the family cooked, ate, and lived, plus two rooms off. One of these would have been the Buttery, which we would understand nowadays as being a larder or pantry, and was probably situated at the rear of where the kitchen now is. The word Buttery replaced the older name of Ambry. The other room would have been the Parlour. Nowadays, we understand a Parlour to be a sitting or reception room, but in the 17C the room was the master bedroom where the master and mistress could go somewhere private to talk and is derived from the French ‘parlez’. It was probably situated at the front of where the kitchen is now.

Upstairs would have been lofts open to the roof and used for the storage of fleeces and grain etc. plus sleeping accommodation for the children. Access to the loft would have been via a stairway, possibly the current one. The Women’s Wash Room is a later addition, and the doorway leading from the stairs to it would have originally been a small window to admit light onto the stairway.

The external walls would have used irregular boulders, built either dry or with clay, with the walls themselves sitting on a plinth running around the building and extending some 9 to 12 inches out from the wall - see below.

Occasionally, instead of a plinth, the wall would splay out down to the ground as in the example below from the downstairs dormitory wash room. Note: Although this is now an internal wall, at that time it would have been an external one.

At the corners of the building where the walls met, the corner stones, or quoins, would have been built out of larger irregular boulders, and at the base there would often have been a large boulder protruding beyond the building – see to the left of the entrance.

The roof timbers would have been substantial enough to support heavy local slates, the lighter Welsh slate then not being readily available, and some of these can still be seen in High House, though probably not in their original locations. Most of the beams in the Men’s Dormitory appear to be very old as they have stopped chamfers and peg holes, and are typical of the style used in the late 17C. They could have been used to support a similar roof in the same location in Phase 1 or 2, and then re-used in Phase 3 (or possibly Phase 4). There also appears to be 16C beams split along the centre to make two beams. Some of the beams appear to have recesses cut to support cross members in a different orientation.

In the Common Room near the kitchen wall corner is a vertical beam supporting a cross beam. It has stopped chamfers and recesses, indicating considerable age, possibly contemporary with the original building. It was probably used in Phase 1 or 2 in a horizontal position to support say floor joists, and then re-used in Phase 4 in its current position.

Investigation has taken place regarding the possibility of Carbon Dating some sample timbers. The cost of a sample would be approximately $595, and the results would be difficult to interpret because to correctly age the building, the timber sample would need to be taken from the outside of the tree.

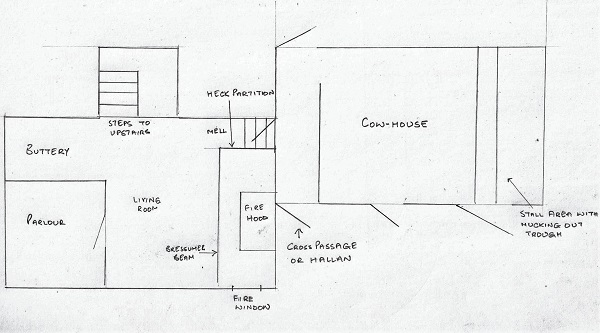

The following diagram was kindly provided by Andy Lowe, the former Built Environment Conservation Advisor with the Lake District National Park Authority, whose invaluable help in compiling the history of the building is much appreciated.

The standard arrangement at the fire end of the Firehouse is shown in the diagram above. The entrance would be from the Hallan, where the current door to the Men’s Dormitory is now. The passage into the Firehouse was called the Mell, and it was separated from the fire area by a short partition called a Heck. Heck partitions were either masonry structures or made of oak panelling, and their purpose was to prevent undue drafts from the outside. The current wall in that position could well be the original Heck.

The space between the Heck and the opposite outside wall was the fire recess or chimney corner, and these were often deep enough to accommodate a seat of some sort, either a high backed settle or a simple fixed wooden bench. In that respect, the two seats that we currently have on either side of the stove are very much in keeping with that tradition.

The fire would have been of peat on a hearth stone raised very slightly above the floor level, and they were often kept burning continually. Above this fire would have been a smoke hood which tapered up into the space above. This could have been into the loft above (now the Members Room), or the Firehouse could have been open to the roof. This hood would have been of stone, or of lath and plaster on a wooden frame. No remains of this smoke hood can be seen.

The front of the hood would have rested on an oak beam running across the front of the fireplace and possibly supported at the ends by vertical oak beams. The distance of this beam from the fire wall is remarkably consistent in similar houses of the period only varying between 4 and 6 feet. The current beam running across the front of the fireplace is in the correct position for this purpose, but is a modern beam probably installed in Phase 4.

The smoke hood would have tapered into a round chimney supported on corbels to counterbalance the stack. The remains of these corbels can still be seen by going up into the loft - see below.

The upper parts have been removed as have the outside remains of the stack, probably during Phase 4 when the rendering of the outside wall above the Men’s Dormitory took place.

A small fire window in the outside wall near the fire provided light to the cooking area. Many of these windows were unglazed, to provide a draft to the fire, but it seem reasonable to expect some kind of shutter to enable the worst of the weather to be shut out. Very few would have been glazed. The walls would taper from the inside to the outside. There is a current window in the correct position, but it has been enlarged and a pane added, probably in Phase 3 or 4.

Between the fire and the fire window, there would normally have been a small spice and salt cupboard, the heat of the fire keeping the contents dry. This is no longer visible, and we have no evidence for its presence.

The 18th Century

We now come to a ‘gap’ in the documentation in that we cannot recognise the succession and ownership of High House. Denis Mollison speculates that this is because they may have been dissenters, as it was the church at that time that kept the records of births, marriages, and deaths etc. The Fisher family of Seatoller House are also missing from the registers around this time, and that's presumably because they were dissenters as the National Archives have an application in 1705 to use Seatoller House for dissenting services. Seatoller House is situated at the foot of Honister Pass, and is now a guest house - see below. In John Marius Wilson, Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales (1870-72), he notes that there were dissenting chapels at Rosthwaite and Grange.

The documents start again with the marriage of Johnathan Brathwaite, who lived at High House and Alice Wilson of Stonethwaite in 1707. We know that Johnathan had a sister Mary who married Mr. Harris from Whitehaven, but we know nothing about his ancestry. However, we do know that Johnathan and Alice had five children. The eldest Isabel was born in 1708, and died no later than 1750. The second child Thomas was born in 1714 and married Hannah Bolton in 1743. In 1744 they had a daughter Mary but unfortunately, Hannah died in childbirth. The third child William was born in 1717 and died in 1739 aged 22. Sara was the fourth child, and she married Jonathan Jopson, a family name associated with Seathwaite. The fifth and last child was Mary who married John Pearson from Thornthwaite. She died in 1778 having given birth to nine children.

Jonathan Braithwaite died in 1750, and in his will made that year he describes himself as a yeoman “of Highhouses”. Besides various amounts of money that he leaves to his children, he also did “bequeath unto my Son Thomas Braithwaite to All my Household Goods and

Husbandry Gear except my Close Chist [chest] and another Chist [chest] that my Wife uses. Also I Give and bequeath to my Wife Alice Braithwaite two Bedsteads and Bedding to them and one Iron Pot, and One Iron Pan. Also I Give and bequeath unto my Son Thomas Braithwaite All my Cattell and Heaf going Sheep”.

The succession duly passed to Thomas, and it was this Thomas that re-built High House in 1747. Presumably his father Johnathan had been ill for some time, and the farm effectively passed into Thomas’s control some years before. The difficulty in identifying who-is-who is illustrated by a reference in the book Seathwaite Wad to a John Braithwaite of Seathwaite being a co-owner of the Wad mine and who chased some men as they tried to steal the valuable ore from the Wad mine. This sounds like it could be the same Johnathan Braithwaite who lived at High House, but he died in 1750 so it can’t be.

When Thomas Braithwaite died in 1797 [?], the Braithwaite succession ended as there was no son to continue the farm. There is no record of Thomas marrying again after the death in childbirth of Hannah, and the only other son of Johnathan and Alice was William who had died some years earlier aged 22. The will of Johnathan mentions that the flock of sheep belonging to High House now belonged to Seathwaite Farm, where it still preserves a separate mark. This could have happened as there was no male line to pass the farm to, and the merging of holdings as noted above took place.

Mention was made above of Thomas Braithwaite rebuilding High House in 1747. A National Trust survey mentions a date stone showing TBD 1747, and this is possibly shown as a diamond shape over the fire window on the earliest photo we have of High House which we think dates from 1913 - see below.

We also know that in 1961, Guy Plint reported that an obituary notice for Stella Joy in the FRCC Journal made reference to the “keystone taken from High House before its reconstruction”. The then Secretary had checked with Miss Joy's executors but no mention of this stone was made in her will. The whereabouts of this keystone is one of the mysteries at High House.

We do not know the nature or extent of this re-building work, but we can examine the building for evidence. By the mid 18C, walls were being built using split boulders, visible as a dark colour, interspersed with slate to make building easier. They were bonded using lime or cement. The back outside wall of the Men’s Dormitory is an excellent example of this technique, though this is actually a wall rebuilt in 1966 - see below.

During the 19C, the corners of the walls, the quoins, changed from the irregular boulders of previous building phases to large slates stood on their sides.

By this time, coal was becoming widely available as a result of the west coast ports of Whitehaven and Maryport. The burning of coal requires a greater quantity of air for combustion and narrower flues to produce strong draughts, so there was a gradual move away from open hearths below smoke hoods towards metal grates below flues. Hence at this time, or later in this phase, the open hearth stone and smoke-hood would have been replaced with some kind of fireplace or even a fire range, and the fire window would have been glazed.

Traditionally, floors were either paved with pebbles or loam, but by the mid 19C, they were almost universally replaced by stone flags. Inspection of the floor below the wooden floor in the Men’s Dormitory shows areas of what could be small cobbles, indicating that this building was intended for animals and not humans - see below.

Sometime in the 19C, the parlour would have been converted to a small sitting room and a fire added, with the master bedroom moving upstairs. During the kitchen alterations in 2006/7, a bricked up fireplace was revealed, and as it was shown on the 1934 architect’s plans, it must have been bricked up as part of Phase 4.

Also during this phase, the door to the Hallan would have been blocked up and the entrance moved to the right. A photo taken in the early 1900’s has recently come to light from the Mabel Barker collection showing a doorway in the middle of the front Men’s End wall.

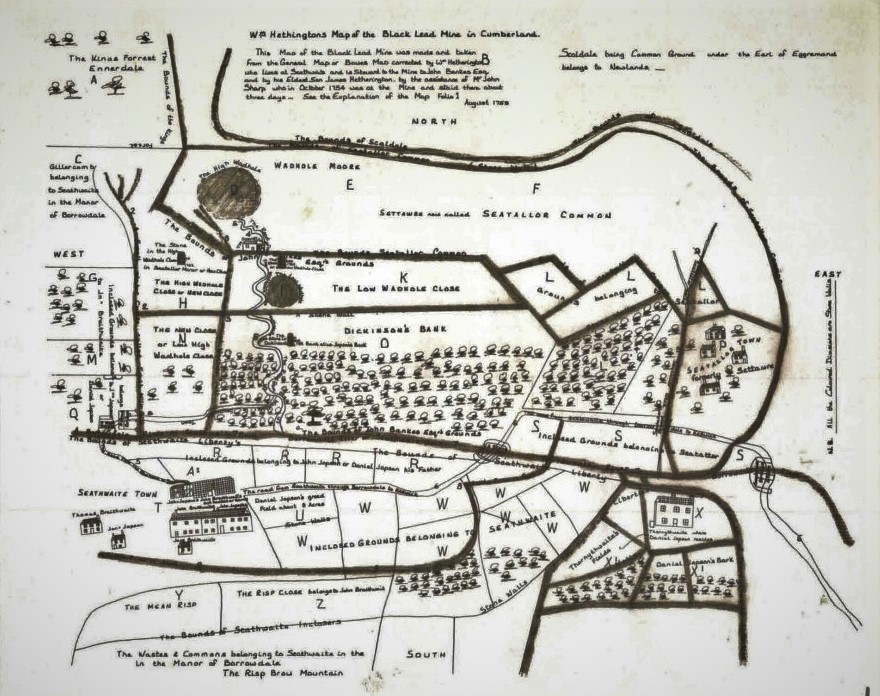

| In 1754, William Hetherington was promoted to the position of Mine Steward at the wad mine, and in 1759 he produced a map of the area around the wad mine, helped by his son James Hetherington. This schematic map shows High House occupied by Thomas Braithwaite, and nearby a house occupied by John or Johnathan Jopson. It is not clear which building that is, but is presumably one of the buildings shown below as group 3? It can't be Rain Gauge Cottage as it wasn't built until later. |

|

Up to this time, we have had no evidence for the outline shape and orientation of High House, and we have had to use supposition for this purpose, but in 1766 there come the first documentary evidence. In that year, John Harrison of Chapel House in Rosthwaite, who was the Clerk of Ruthwaite [presumably Rosthwaite], was commissioned to draw up plans for a mine steward’s house at Seathwaite. The house was known as Beck Cottage and faced west, thus providing good views of the mine. The building was completed in 1767, and is the cottage we now know as Raingauge Cottage. Since that time, a barn has been added on the south facing side, and a single storey extension has been built on the north facing side. See photo below taken from Ian Tylers' book 'Seathwaite Wad'.

In 1769, Henry Bankes esq. the owner of the Wad Mine (or the Black Lead Mine as it was then known), further commissioned John Harrison to create a map of the mine and Seathwaite, and the area around it for up to two miles. The actual ownership of much of the land around the mine had been disputed for many years, and this was an attempt to settle the matter once and for all. It is interesting to note that one theory for the origin of the expression 'black market' derives from the illicit dealing in this black lead. The part of the map showing High House is shown below. |

|

The “References to the Pillages of and Grounds adjacent to Seathwaite” on the map show that the plots labelled as 4 on the map are “High House belonging to Thos Braithwaite”. Two items should be noted. The first is that the House and the Cow-House are aligned with one another, and we should assume this is merely inaccurate drawing, albeit on a map that otherwise appears to be drawn accurately. The second are the two plots at right angles to the Cow House. Are these buildings or enclosures?

|

|

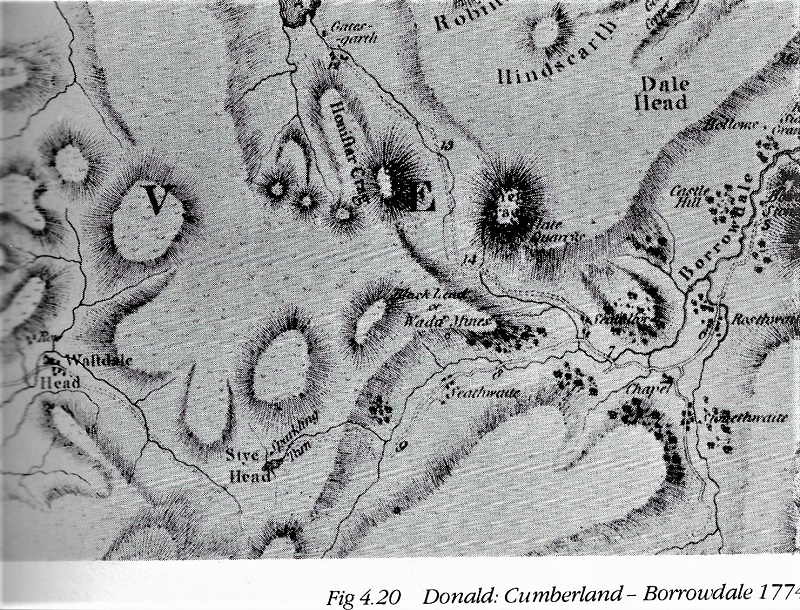

In his 'Roads and Trackways of The Lake District' Paul Hindle says that Thomas Donald surveyed his map of Cumberland in 1770-1, engraved by J Hodskinson, and published in 1774. The section concerning us is shown below. The accuracy of the map is much better than previous ones, but not perfect as he places Sprinkling Tarn at Stye [sic] Head. Looking at High House, it is shown as two black blobs rather than the one blob as expected. He could have been indicating two separate buildings, or more likely two parts joined - the house and the cowhouse. |

|

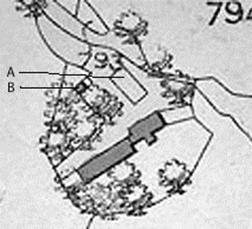

The next map to give us some evidence is the OS map sheet 76 from 1861, shown below, and this is full of interest. On this map, the misalignment of the House and the Cow-House can be plainly seen, but the length of the Cow-House is more than half as long again as the length of the House, meaning that at some point the Cow House was reduced to its current size.

Appearing on this map, but absent from the 1769 map, is the rectangle opposite the House labelled A where the lawn is currently. Presumably this would have been an enclosure of some type, as if it was a building it would have been coloured like the main building. A third point is that the two plots at right angles to the Cow House in the 1769 map above are missing. Finally, there is a small coloured area labelled B. Could this have been a privy?

Up until the middle of the 18C, the enclosure movement had been going on in a piecemeal fashion, but in the second half of the century it became more systematic and was achieved through agreement between tenants or by Act of Parliament. One of the major effects of this increase was that it marked the beginning of the decline of the statesman farmer, and as the small estates were incorporated into larger enclosures so the number of farmers declined as the size of the land holdings increased. This phenomenon, while it has its origins in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, is still continuing today with declining numbers of farms holding increasingly larger areas of land, due in part to the farm subsidy now being paid on acreage rather than the number of sheep. A measure of the decline in the number of farms in Borrowdale is shown by the following -

In 1418, there were 41 farmsteads in Borrowdale, by 1829 this had halved to 21 farms, by 1925 it was 19 farms, and by 1938 there were 18 farms including 2 of over 150 acres. In 2006 there were 12 farms listed for Borrowdale in the Shepherd’s Guide.

Year |

1418 |

1829 |

1925 |

1938 |

2006 |

Farmsteads |

41 |

21 |

19 |

18 |

12 |

By the C18, tourism was starting to bring visitors into the area, and in 1769, the poet Thomas Gray made a ten day tour. He travelled to Borrowdale, and being much impressed by the grandeur of the scenery, says in the romantic language of the time "There is hardly any road but the rocky bed of the river ...The dale opens about four miles higher until you come to Sea-Whaite (where lies the way mounting the hills to the right that leads to the Wadd-mines) all further access is here barr'd to prying Mortals, only there is a little path winding over the Fells, and for some weeks in the year is passable to the Dale's-men....For me I went no futher than Grange.

That description of the isolated nature of Borrowdale in general around this time is re-enforced by a description of the valley and its residents from Hutchinson’s History of Cumberland in 1794, where he states that “the surface of the ground was very little cultivated and that even by the late 1760s a cart or any type of wheeled carriage was totally unknown in Borrowdale”.

Father Thomas West in 1778 takes a different view to Thomas Gray above."The road into Borrowdale is improved since his time [this is only 9 years later!]....it serpentizes through the pass above Grange, and though upon the edge of a precipice that hangs over the river, it is nevertheless safe....Bowdar-stone [sic] on the right in the very pass, is a mountain of itself, and the road winds round its base" . This seems to imply that the road he travelled on was passed the Bowder Stone.

Borrowdale remained a partially isolated valley until 1842 when a road was cut directly through the valley from Keswick, replacing the route via Watendlath.

The 19th Century - The end of High House as a farm.

Although the enclosure and improvement of the common and waste land can be viewed as important developments, bringing Cumbrian agriculture practice up to the same level as that found in the south, there was a price to pay. It heralded the final decline of the yeoman farmer who lost rights to common pasturage and whose small estates were swallowed up.

We can assume that High House ceased being a farm after Thomas’s death, and became merely a dwelling, and probably because of this the documentary evidence for occupation becomes sketchy. It also probable that ownership of High House as a dwelling passed to the owner of Seathwaite Farm along with the sheep.

The next mention we have of occupation is a reference in the Bankes family archive (the owners of the Wad mine). In the mine archive, we have a Joseph Glover mentioned as a Miner and living at High House in 1818. Nick Stuart who is now living in Threlkeld [2010 - now moved back to Hampshire] is a descendant of a Charles Stuart, and from his research we have the age of Joseph Glover at that time as 67. This Charles Stuart senior married Sarah Birkett the daughter of Joseph and Dinah Birkett, and all four of them moved from Furness to farm Seathwaite Farm in 1818. Charles became a “Graphite Black Lead Miner”, and stayed in the valley the rest of his life. There is a record of him in 1825, listing him as a Miner in the mine records. In 1827 Charles and his wife Sarah have various children in the valley, and probably in Seathwaite.

In 1841, we have the first census return, though High House is not listed separately but included under Seathwaite. It lists 6 households containing 36 people in Seathwaite, with the heads of the various households being John Birkett - Farmer, Thomas Birkett or William Birkett – Agricultural Labourer, Dinah Birkett (the widow of Joseph Birket who died in 1836) – Cottages (does this mean that she rented rooms in her cottage, or that she lived in what we now know as Seathwaite Cottage?), James Bennett – Black Lead Miner (first noted in Mine records in 1803), Charles Stuart – Agricultural Labourer, John Dixon – Black Lead Miner. Presumably one household equates to one dwelling. John Dixon had taken over the running of the mine in 1837 following the death of his father William Dixon Snr, and around this time the mine company had a house built at Seathwaite (possibly for John Dixon?). Which building this is we don't know.

.jpg)

The photo above is from Stephen Edmondson, a member of the Seathwaite Edmondson family who now lives in York. He says that the gentleman front left with the tall hat is supposed to be John Dixon above (1787 - 1866) who followed his father William Dixon and grandfather Thomas Dixon as steward at the wad mine.

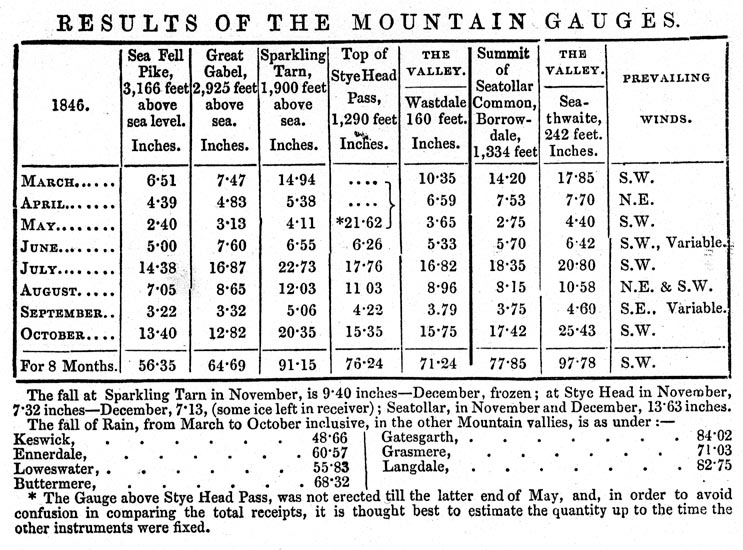

In 1844, Dr John Fletcher Miller, the respected C19 meteorologist and Fellow of the Royal Society was living in Whitehaven. He became aware of the high rainfall in the Lake District and set up over 26 rain gauges at various locations, and in 1846 at different altitudes.

The Met Office have in their archives his published figures for 1846 showing that Seathwaite received 143 inches compared with Kendal on 52 inches and Manchester on 33 inches. He also showed that precipitation increased up to an altitude of 2000 feet after which it decreased.

London based meteorologists first scoffed at the figures as it was widely believed at that time that it was not possible to have more than 100 inches of rain outside the tropics. But the extraordinary numbers continued to appear and they were eventually accepted.

Some of his figures are shown below for 1846. Interestingly, the rainfall in Seathwaite at 421 feet (not 242 feet as noted in the table) is nearly twice as much as that on Scafell Pike at 3,210 feet (not 3,166 feet as in the table) - 97.78 cf 56.35

It is thought that he paid shepherds to take the measurements, and certainly at Seathwaite he used the above John Dixon. It is perhaps from around this time that the name of Beck Cottage changed to Raingauge Cottage. According to the Met Office, there are still rain gauges at Seathwaite Tarn GR 324926E 498385N, and Seathwaite hamlet itself, GR 323579E 512167N. The highest rainfall in England is recorded in Borrowdale by the Sprinkling Tarn gauge where an annual average of 185 inches falls. At the Seathwaite hamlet gauge, the amount reduces to 131 inches and the figure steadily reduces as one travels down the valley, with just over 100 inches in Rosthwaite, 90 inches in Grange, and 57 inches in Keswick.

Rain gauge in the garden of Rose [sic[ Cottage, Seathwaite, c1890's Taken from https://www.lakelandroutes.uk/local-history/the-wolfman-of-eagle-crag/ |

The continued opening up of the Borrowdale Valley led to a steady growth in its population. There were 342 people in 1801, growing to 452 in 1851 and 506 in 1891.

In the 1851 census we have the number of households in Seathwaite increasing to 8 with 34 people, consisting of John Birkett – Farmer, Thomas Birkett – Farm Labourer, William Birkett – Farm Labourer, James Bennett – Former Black Lead Miner (he was now aged 71 and his son John aged 32 was now a Lead Miner), Birkett Jenkinson – Stone Quarryman, John Dixon – Steward of the Black Lead Mines, Charles Stuart – Labourer. The road system was also improved and in 1842 a road was cut directly through the valley from Keswick, replacing the route via Watendlath.

In 1861 we see a reduction to 7 households with 32 people. These are now John Birkett – Farmer, Thomas Birkett – Black Lead Miner, Elizabeth Birkett – Head of household, Sarah Bennett – Cottages, Thomas Earl – Labourer, Charles Stuart – Black Lead Miner.

In 1866, we have a reference to one of Charles Stuart’s daughters – Mary Ann – dying aged 22 at High House. From this, we can infer that the last household in each census return is probably living at High House. Charles’s occupation is now that of Husbandman (Tenant Farmer) presumably because the mine had laid workers off (the mine officially wound up in 1891). In 1870, Charles Stuart’s wife Sarah dies aged 77, and Charles went to live with his daughter in Grange where she ran the local Grocer/Post Office.

The census for 1871 shows a furthur reduction to 4 households with 18 people: John Birkett – Farmer, Thomas Earl – Labourer, Thomas Birkett – Farm Servant, William Jenkinson – slate Quarryman.

We don't know which slate quarry William Jenkinson worked in but it could well have been Honister. New owners took over in 1879, and the future must have looked bright as various plans were put forward in 1883 to extend the workings, including two railway projects. The Honister Crag Railway was a line from the summit of Honister Hause, across the fell side to the foot of Honister Crag and then diagonally up the Crag face to a point almost at the top: it took 13 years to complete and lasted 30 years. The Braithwaite and Buttermere Railway was a proposal to link the quarry with the mainline network at Braithwaite near Keswick. At that time nine horse drawn cartloads of slate were taken each week to Cockermouth via Buttermere, and this proposal was to speed up that process and increase capacity for the future. The Bill went to Parliament but failed due to environmental opposition.

.jpg) |

Early in 2008, the Club had a communication from a Barbara Brotherton regarding her family history. She told us that her grand-mother Isabell Martin lived at High House in 1880, and this is confirmed in the 1881 census where we have 5 households with 29 people: Wilson Birkett – Farmer of 300 acres, Elizabeth Dixon – Farmer, Thomas Earl – Labourer, not employed (he was now aged 80), Thomas Black – Quarryman, William Clark – general Labourer, unemployed (he was aged 67). For some reason, this census return has High House listed separately and shows Benson Martin, Quarryman, as the head of the household of 7 people, including 2 “boarders”, John Mossop from Lancaster, and Anthony Atkinson from Langdale. Included in the household is Isabella Martin, the daughter of Benson Martin, aged 2. Soon after this, the Martins left High House to live in Rosthwaite, with Benson still working in the slate quarries.

In 1897 Benson Martin, aged 51 years old, died at Low House, Coniston. On the death certificate it stated that he died from Acute Pneumonia and Asthonia (Asthenia is a condition in which the body lacks or has lost strength either as a whole or in any of its parts). However Barbara Brotherton’s mother (Benson's grand-daughter) maintained that he had been killed in an accident while at work in a slate quarry. Perhaps he developed pneumonia as a result of the accident.

The 20th Century - The End of Residential Occupation

We have no further documented record of occupation at High House after the 1881 census, though one of the households in the 1891 census may have been High House. It gives 6 households with 29 people, consisting of John Richardson – Farmer, William Hughes – Lead Miner, Miles Bainbridge – Slate Quarryman, Thomas Pepper (from Langdale) – Slate Dresser, Johnathan Sloop – Quarry Labourer.

By 1901, the hamlet had again shrunk, with only 3 households and 18 people: John Richardson – Farmer, William Hughes – General Labourer, and John Jackson – Slate Quarryman. Besides himself aged 51, John Jackson's household consisted of Annie Isabel Jackson, Wife, aged 38, Fred Jackson, son, aged 4 days, and Hannah Gill sister, aged 60

The 1911 census data shows three inhabited houses for Seathwaite, with the last house inhabited by Addison Pepper and his family. Addison was shown as being a Quarryman Splitter, and originating in Langdale. It is thus likely that High House was unoccupied after about 1895.

During this period, we can see three links between Seathwaite and Langdale.

1.

George Birkett [Died january 2017] who lived in Little Langdale says that his grandmother was a Richardson and came from Seathwaite. This must have been the Richardson family in the above census. She could have been this entry in the 1911 census - Richardson, Sarah Ann, Daughter, Single, female, aged 32, with her occupation as farmers daughter, and originating from Grasmere.

2. Georges mother was Mary Birkett nee Myers. In the Ambleside Oral Archive, she says that she was born in Seathwaite in 1906 and moved to Langdale in 1913 following her fathers return from America, having gone there to find work. The 1911 census gives her thus - Myers, Mary Granddaughter [of John Richardson] Female, aged 4

Her father became a tenant farmer at Wall End, Great Langdale, but later in 1913 there was an outbreak of diphtheria amongst children in Langdale and seven of them died. To prevent Mary Birkett from catching diphtheria, she was sent back to Borrowdale for safety, eventually returning in 1916. She eventually married Bob Birkett, the brother of Jim Birkett the noted climber.

3. James Edmondson, the nephew of the first Stanley Edmondson to run Seathwaite Farm, worked at Seathwaite Farm for his Uncle Stanley until he got the tenancy of his own farm in Lorton in 1954, moving later in 1966 to Great Langdale where he still lives.

The table below summarises the census returns for the years above, and illustrates the marked fluctuations in population, probably due to the varying degree of success of the Wad mine. The population currently living at in the hamlet is also shown for comparison.

Census |

1841 |

1851 |

1861 |

1871 |

1881 |

1891 |

1901 |

1911 |

2009 |

Households |

6 |

8 |

7 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

4 |

People |

36 |

34 |

32 |

18 |

29 |

29 |

18 |

15+ |

8 |

The extent to which people were moving around at this time in search of work is shown by the originating place of each person in the census returns. In the 1901 census we have the following as their originating place – Caldbeck – 2 people, Ambleside – 8, Ireby – 1, Holywell – 1, Keswick – 2, Lamplugh – 1, Borrowdale – 2, Manchester – 1.

It should be remembered that Census Returns only give the main employment of each person. Trade Directories and Gazetteers on the other hand will list any trade or business activity being carried on. From these sources we see that in 1901, William Hughes has lodgings to support his lead mining activities, and that John Richardson has apartments to support his farming. John Richardson was 72 at that time, so it is not surprising that by 1921, we find a new name running Seathwaite Farm: John Edmondson – Farmer, with more than 150 acres. This is the first appearance of the family who are still running Seathwaite Farm.

We saw above that High House doesn't appear to have been occupied after the 1880's, but there were some temporary visitors. Mabel Barker was a pioneering teacher, born in Silloth, who founded her own school in Caldbeck, where children were taught, above all else, to enjoy and to cherish the outdoors. She became a noted climber and mountaineer, the first lady to climb Central Buttress on Scafell and the first lady to complete the Cuillin Ridge Traverse. She was a larger-than-life character whose full story is told in And Nobody Woke up Dead by Jan Levi (Ernest Press). In 1913 she made the first of many camping trips to the Lakes with some of her students from Saffron Walden, often camping at High House. She called them the Walden Gypsies. |

|

| She met up with Millican Dalton, another larger than life character, who spent his summers in a cave on Castle Crag. Her photographic collection shows them climbing on Seathwaite slabs, calling it 'our gymnasium', and many photos of them camping in the grounds of High House. There are also some enigmatic pictures of a group around a campfire inside a barn which her notes refer to as ‘our original accommodation’, almost certainly what is now the large downstairs dormitory. One album is dated 1924. One of the photographs is of another camping meet at High House, with the sad hand-written note underneath saying, ‘Note the tree on our house’. It’s the clue that tells us when a falling tree demolished High House. |

This photo is from Mabel Barkers collection dated 1913, and is the earliest photo we have of the inside of High House. There is a reference to them using the cowhouse (now the downstairs dormitory) but this photo appears to show the walls rendered, or at least limewashed, which suggests that Mabel and her chums are in the part set aside for humans rather than beasts. |

'K Fellfarers' acquire High House In March 1931 a General Meeting was held at the factory of Somervell Bros (later known as K shoes) to present to interested employees the idea of a Hostel in the Lake District for the use of those workers who wished to enjoy climbing and walking the Lakeland countryside. About 80 people attended and support for the idea was "very strong”. Locations were discussed and Borrowdale was the final choice. A Hostel Committee was set up, with Building and Finance sub-committees. The instigators of that meeting were Leslie Somervell and William Ingall. Subsequently, with the help of Harry Whitehead and Edward Caton, these two were the main driving force of the whole project and the founding of 'K Fellfarers'. In an article called "21 Years After", written for The Eyelet, the K Shoes in-house magazine, Madge Thexton wrote in 1955 of William Ingall: "I wonder if anyone has ever given any thought to just how many miles he must have walked and how many hours he must have given, ever on the look-out for a suitable building to convert into a climbers' and walkers' hut or for a site on which a building could be erected." William and others combed the upper valleys of Borrowdale for suitable buildings, without result, until someone suggested the derelict house on the left of the Sty Head Pass as it leaves Seathwaite Farm, known as High House. The building was inspected, but proved to be merely a ruin, a large tree having fallen across the house portion, bringing down the entire roof and most of the front and back walls. Mr. Leslie Somervell approached the owner of the property, Mr. Walker of Seascale. It was recorded that Mr. Walker was “favourably disposed to the venture, and was willing for us to rebuild the ruin should we wish. At the same time he discouraged us from undertaking such a task, and offered us the option of using a fine terrace of ground on the Sty Head side of the old house.” William Heskett & Son, of Penrith, Land Agents for Mr Herbert Walker, offered the "fine terrace" in the adjacent field to Somervell Bros. on the 9th May 1931 at an annual rent of £2. The site was described as a plot of land “adjacent to the New House ruins (sic)”. On the 30th May 1932, the Hostel Committee asked Humphreys Ltd.,who had built the Honister Quarry buildings, for the price of “a hut in the Borrowdale district for the use of our employees, (male and female) when participating in hill climbing excursions”. Humphreys quoted the price of £825, the price of a building that is now the Honister YHA building, but pointed out that it didn’t include the roofing of Slate because the Slate Quarry had done that work themselves. The specification for the building and a blueprint of the plans is contained in the Club Archives and a copy of the blueprint for the buildings is shown below. The building of the new property was seen as too expensive, and so commenced the re-building of High House, and its eventual opening on May 5th, 1934. |

Down at the farm - The Edmondson family |

|

The photo above is again from Stephen Edmondson, and shows his great grandfather John Edmondson in Seathwaite farm yard with his daughter and granddaughter. |

| (Old) Stan above died in 1985, and by then his son (Young) Stanley below was running the farm along with his wife Nancy. Nancy died in 1998, and Stan 5 years later in 2003, when one of their sons Peter took over the tenancy. Their other son Stan was meanwhile running the trout farm in Seathwaite, and eventually he handed it over to his son Stephen Stanley. Stephen has since given up the trout farm and is working as a stone waller. |

.jpg) |

An obituary of 'Young' Stanley from the Cumberland and Westmorland Herald is given below - Noted Borrowdale farmer, sportsman and hunt followerDate: Saturday 22nd November 2003

BORROWDALE farmer Stan Edmondson, known for his calm and gentle manner, died on Sunday at the age of 76. He was also a member of Keswick mountain rescue team for many years and would tell his family of the many rescues he had been on, which he could still remember in great detail. He was also a keen supporter of the Blencathra Foxhounds and loved to go out hunting. Mr. Edmondson had been a director of Mitchell's Auction Company, at Cockermouth, since 1986 and he was described by the chairman, Peter Greenhill, as a "phenomenal man". Mr. Greenhill said: "His knowledge of sheep was legendary and he was a wonderful asset to the mart. He was a calm and gentle man and in all the years I have known him I have never seen him lose his temper." He praised Mr. Edmondson for his work with the Cumbria federation of Young Farmers' Clubs. "We have hosted Young Farmers' meetings for many years and Stan would think nothing of bringing down sheep fully dressed and ready for them to judge, just for the evening. He would carefully explain things to you without belittling you," Mr. Greenhill added. "He was a very special man and we were privileged to know him. He will be missed by so many people. One of Stan's dreams was to see the new auction built and up and running, and he has done that." Mr. Edmondson's first wife, Nancy, died some years ago but he found happiness again with his second wife, Janet. He also leaves three children, Peter, who has run Seathwaite Farm since his father's retirement; Stanley, who runs the fish farm next door to Seathwaite; and Janet, who lives in Cyprus. He had seven grandchildren and four great grandchildren. Mr. Edmondson had recently returned from a holiday in Cyprus, staying with his daughter. Janet Edmondson said: "It was the first time he had been abroad and flown and he loved it. I am so glad he went out to see his daughter and had a wonderful time." Despite having never travelled abroad until this year, Mr. Edmondson was well travelled in Britain. He had covered the length of Britain over the years, from Land's End to John O'Groats, always visiting farms along the way. Mrs. Edmondson added: "Farming was his life and he loved Borrowdale and never wanted to live anywhere else. I look out on the fells since his death and it's like they are weeping for him. "He was still the tenant on Seathwaite Farm when he died and he was very proud to say he was one of the longest serving tenants of the National Trust." Mr. Edmondson’s funeral service was held yesterday at St. Andrew's Church, Borrowdale, followed by a burial in the churchyard. Peter Edmondson below has been running the farm since 2003 following the death of his father. |

|

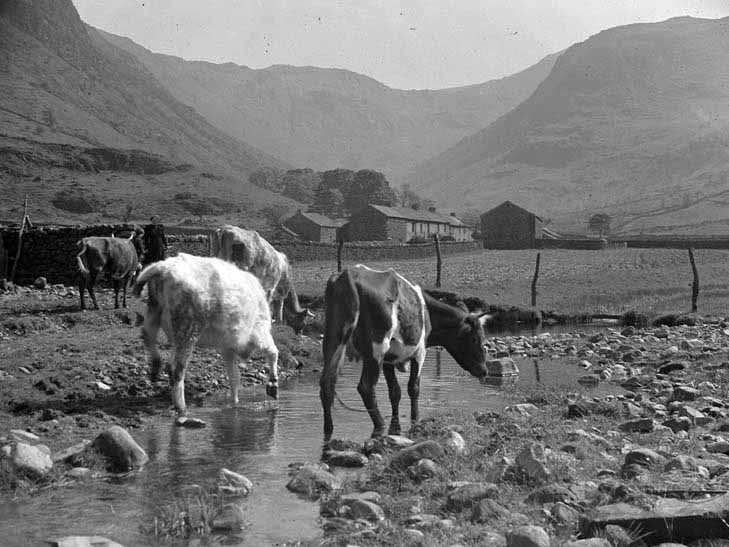

The photo below is taken from the Joseph Hardman Archive kept in the Museum of Lakeland Life in Kendal. He took his photos between the 1930's and the 1960's, recording scenes of Lakeland life. This one shows cows in a field with Seathwaite behind. |

|

This photo is from the clubs photo archive, and is labelled 1940's |

|

Taken by Kenneth Shepherd before the WW2, it is labelled "Borrowdale Bracken for Bedding" and says 'the father and son of Edmondson's Farm, Seathwaite, loading the bracken from the lower fell slopes. Nowadays, straw has replaced bracken for bedding except in very mountainous areas" |

Again taken by Kenneth Shepherd before the WW2, this is labelled "Borrowdale Farming Mechanics" and says "A photo from the early war years [WW1?] where as much land as possible had to be tilled....these men of Seathwaite - ploughman Noble Bland (left) and Stan Edmondson, with Bill Edmondson dsriving,modified their old Austin pick-up for its new task". |

The 20th Century - The NT acquires High House, Seathwaite Farm, and Rain Gauge Cottage. The history of the ownership of Seathwaite Farm, High House, and Rain Gauge Cottage prior to this date is of interest. Up until 1836, the property had been in the ownership of the Birkett family. In that year, the incumbent Joseph Birkett died leaving the estate in trust to his son John and two others. They sold it in 1838 to Joseph Fisher, the brother of Abraham Fisher of Seatoller who eventually inherited. When Abraham died in 1868, his trustees sold the farm to H C Marshall of Derwent Island. After his death in 1895, his trustees sold the farm to John Musgrave of Wasdale Hall who was interested in the proposal to build a road over Styhead Pass and so wanted to own the land on either side of the pass. |

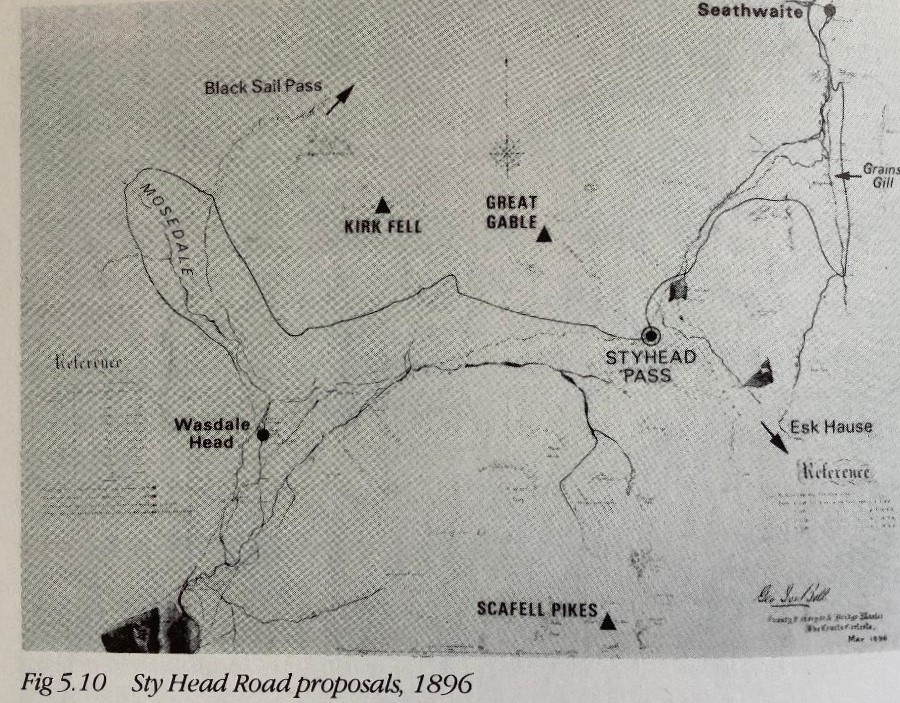

In 'Roads and Trackways of the Lake District' Dr. Paul Hindle states that In 1896 the self-taught County Engineer, George Bell, actually surveyed a route, which if it had ever been built would have been one of the most curious in Britain. From Wadale Head, he proposed to take the road around the head of Mosedale at a gradient not exceeding 1 in 12, and generally only 1 in 20, thus reaching 1,000 ft before it even turned towards Sty Head. In descending into Borrowdale, it would take a similar line to the current path, but crossing Grains Gill half a mile above Stockley Bridge. See below for a map of the proposal taken from Paul's book. |

|

In 1897, a meeting was held between Keswick Urban District Council, Whitehaven Rural District Council, and others to discuss building this road and a resolution was passed giving full backing to the concept. The resolution was seconded by this same J Musgrave who referred to the project as “an admirable way of commemorating the Queen's extraordinary reign”. The idea was to open up a remote and inaccessible part of Cumberland, and inevitable led to an acrimonious dispute between developers and conservationists. One supporter was Lovat Fraser, an artist and London theatre designer, who wrote in 1919 that "..the wildest and grandest piece of scenery in England ought to be visited by tens of thousands of humble folk who can never hope to see the Alps or Himalayas"; a very familiar argument that is still used today. |

When the Musgrave Wasdale Hall Estate came up for sale in 1920, it was split up into 25 Lots of which only 9 Lots were sold. Herbert Walker bought the residue, including Seathwaite Farm forming Lot 20, and with it came the titles of Lord of the Manor of Wasdale, Lord of the Manor of Borrowdale, Raw Head Farm, Napes Needle, and many other mountain tops. In 1944, the National Trust acquired Seathwaite Farm from Lodore Ltd of The Tannery, Whitehaven for the sum of £4,200. This included High House, 614 acres of land, and 1102 heathgoing [sic] sheep. Signing on behalf of Lodore Limited were William Walker, Director, and W A Davidson, Secretary. The Conveyance mentions a previous conveyance made in 1923 between on the first part Thomas Machell, George Hill, Wykeham Parry, Edward Musgrave, John Edward Musgrave, and William Franks, on the second part John Raven Musgrave, the third part Herbert Wilson Walker, and William Walker of the fourth part. The acquisition covered the three main parts of Seathwaite Farm - Seathwaite Farmhouse and adjoining Barn, Seathwaite Cottage, and Seathwaite Farm Cottage, all Grade 2 listed buildings. The acquisition did not include Raingauge Cottage as this was still owned by John Bankes at that time. |

|

In 1981, Henry John Ralph Bankes, late of Kingstson Lacy Wimborne in Dorset, died leaving Rain Gauge Cottage and various rights and 30 acres of land to the NT. To denote the relevant land parcels, an old map was again used, this time from an Old County Cumberland map sheet LXXVI dated 1899. Little has changed, and it is interesting to note that the Cow House still has its long length, implying that it was shortened in the later 1934 alterations. |

|

| His will states that the Cottage formerly in the occupation of C E Hudson, and now in the occupation of Joseph Edmondson, is to be left to the National Trust, together with 22 acres. The cottage was later occupied by Ruth Illman, and in 1993 she was followed by two teachers, David and Elaine Pratt, who are still living there with their two children. |

For the history of the Wad Mine, the best reference is Seathwaite Wad by Ian Tyler, pub 1995, and thanks are given to him for permission to use extracts from this book. The other main reference used is the Bankes family archive. This is located in Kingston Lacy in Dorset, but Rod Muncey, a Fellfarers member, managed to get his hands on it whilst working for the National Trust in the early 1990’s, and photocopied many interesting parts of the archive and filed them with the NT at Grasmere. Thanks are given to the Trust for permission to use these and for access to the rest of their archive. It is interesting to note that most contemporary sources note the mines variously as Graphite, Black Lead, Plumbago, or Black-cawke. The copy of the Hetheringtons map of 1759 was given to me by David, the owner of the Glaramara Hotel. The information on Mabel Barker has been taken largely verbatim from the Clubs Commemorative Book, and a chapter written by Mick Fox who tracked down her part in the history of High House and her remarkable collection of photos. For the information on the excavations below Stockley Bridge, see the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society Transactions for 2001. For information on the the proposals for building a road over Sty Head, see - An important source of information on the history of Borrowdale including the agricultural evidence, was the Historic Landscape Survey carried out by Oxford Archaeology North for the NT and printed in 2007. The meaning and history of place names has used the book 'A Dictionary of Lake District Place-Names' by Diana Whaley published by the English Place-Name Society 2006. Various references to tracks and roads used 'The Story of Borrowdale' by Shelagh Sutton, written in 1961 and revised in 1974. Thw two photos of the Edmondsons were taken from 'Lakeland 50 Years Ago, Volume 2' by Kenneth Shepherd, in the High House library. Another, and growing, source of data is the internet, where individuals carrying out family history searches are willing to share their findings with other interested parties. Thanks are thus due to the following people – |